Summary: trying to see “higher than the ditches that break up the canvas of the land”.

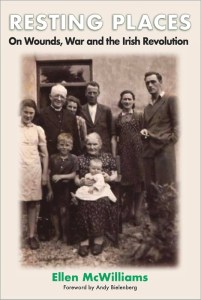

There is an echo of Martin Doyle’s book, Dirty Linen, in Ellen McWilliams’ Resting Places. Like Doyle, McWilliams also uses the literature of Ireland and Britain, experiences from her professional career, and the local history of her home place, in County Cork rather than in County Down, to reflect on wider issues of Irish history and Anglo-Irish relations.

But McWilliams doesn’t stop there. Resting Places is also a remarkably personal work. Her insights on the “big” themes are also prompted by the most domestic ones: by reflections on her relationships with family – both the Cork ones and the English lot – and from her experiences of her own body in her most private moments as a lover and as a mother.

This is apposite: Women and girls were, as McWilliams reminds us, the subject of institutionalised systems of abuse and enslavement, including the Magdalene Laundries and the Mother and Baby Homes, for much of the 20th Century in Ireland. In writing of her own body with such candour she reminds the reader of the strength and fragility of human flesh and how this can be so easily desecrated by bigotry masquerading as righteousness.

By pondering these very intimate aspects of life McWilliams also comes to some of her most important historical insights, ones that can be lost or overlooked in more traditional narrative or political histories. Because so many of the dynamics of war, and particularly of war-crimes, in revolutionary and civil wars have their sources in the domestic sphere: around hearths and kitchen tables, in whispered conversations the memories of ancient ills – of land expropriations, of scorched earth and famine – are kept alive.

And it is one atrocity that perhaps grew from such conversations, the Dunmanway massacre, that lurks at the heart of this book. The country was meant to be at Truce when these killings occurred. But there is no truce on bitter memories.

Between 26 and 28 April 1922, fourteen Protestant men and boys were killed or disappeared around Dunmanway and the Bandon Valley, in the very roads and fields around which McWilliams grew up. These were the families of neighbours killed by the families of neighbours, and indeed the comrades of her own family, which was deeply involved in the struggle for Irish independence.

The fate of two 16 year old boys, Robert Nagle and Alexander McKinley, are particularly difficult for McWilliams to contemplate. A new mother when writing this book, she writes of these boys with an agony of empathy, knowing what it is to carry a child for nine months, tend to him as he grows into his own little person, and to worry that something awful might happen to him. For these boys’ mothers, they awakened to that nightmare.

Perhaps there are still whispered conversations telling new generations why these murders “had to be done.” But McWilliams remembering how Greek tragedy reminds us that crimes that stay buried poison the water of the living, shows true patriotism in confronting this vile aspect of the Irish revolution.

McWilliams is an exquisite writer, warm and frequently very funny. At one point she muses if, in marrying an English scholar of the English civil war, she has actually ended up – at some psychic or metaphorical level – marrying Cromwell himself.

On the evidence of her book, I think the answer is a resounding “NO”. I can’t imagine Cromwell ever fretting over the recipe for soda bread, which her lovely-sounding husband does. Feeding other people is antipathetic to genocide. Cromwell would have hated him.

McWilliams book is an incredibly rich one, fizzing with more ideas that any review can do proper justice to. Read it!

Pingback: Some stocktaking – 3 | aidanjmcquade

Pingback: My best reads of 2024 | aidanjmcquade

Pingback: My most read blogs for 2024 | aidanjmcquade