Famously the Indian sub-continent freed itself from British rule through a non-violent struggle led by Gandhi. However rather than this being a great triumph for passive resistance, the efforts by Congress, the Muslim League, and the Sikh leadership to carve up the spoils more than made up for it in terms of bloodshed: the Partition of India saw one of the most horrendous blood baths of the 20th Century, and the largest forced migration in human history. Sometimes these two things coincided with trains of refugees pulling into their destination stations dripping with the blood of the women, children and men passengers who had been hacked to death in ambushes.

Famously the Indian sub-continent freed itself from British rule through a non-violent struggle led by Gandhi. However rather than this being a great triumph for passive resistance, the efforts by Congress, the Muslim League, and the Sikh leadership to carve up the spoils more than made up for it in terms of bloodshed: the Partition of India saw one of the most horrendous blood baths of the 20th Century, and the largest forced migration in human history. Sometimes these two things coincided with trains of refugees pulling into their destination stations dripping with the blood of the women, children and men passengers who had been hacked to death in ambushes.

In Midnight’s Furies, Nishid Hajari details how the political calculations, petty jealousies, posturings, misjudgements and misunderstandings of the sub-continent’s political leaderships, in particular Jinnah and Nehru, led to the sectarian carnage that engulfed the creation of the modern states of India and Pakistan.

Nehru

Hajari provides a much less sympathetic portrait of Nehru than Alex Von Tunzelman’s fine account of the same period, Indian Summer. For Hajari, Nehru failed in his responsibility as a statesman of obtaining some sort of rapprochement with Jinnah and the Muslim League, and hence undermined his vision of a secular India for all Indians. Hajari also portrays Nehru, at least in the early days of his premiership, as a man in office but not in control. His dream of a secular India uniting Hindu, Muslim and Sikh under a common citizenship bloodily undermined by the extraordinary violence of the period, which his administration seemed powerless to prevent.

Doubtless some of this was spontaneous communal violence drawing on obscure but profound local animosities and feuds. But much of it was not. Each community produced paramilitary forces, many of them highly professional as a result of the large numbers of former soldiers in their midst. These set to the butchery of their neighbours with a relish and ruthlessness that would not have been out of place in the Bloodlands of Eastern Europe a few years earlier.

This killing was frequently facilitated by the failures of Indian and Pakistani police and military to properly intervene to uphold the law. Sometimes the police and army stood idly by. Sometimes they became active participants in the slaughter.

In this regard they were echoing the equivocal leaderships of the two states: Jinnah appears to have missed the logical contradiction of wanting a secular republic for Muslims only. In India Hindus and Sikhs seemed to take their lead less from Nehru and more from Sadar Patel, the States minister in the Indian Union government. Patel regarded the ethnic cleansing of the Muslim population as a good thing, purging the state of potential fifth columnists. He also regarded the neo-fascist RSSS with considerable warmth despite their butchery of tens of thousands ordinary Indians.

Patel

With such equivocal leadership at the heart of government it is unsurprising that so many police and troops turned a blind eye to the atrocities. To his credit, when able to do little else, Nehru time and again sought out and faced down Hindu murder squads, striving to personally halt the killing which so much of his own administration was acquiescing in. Order only finally began to be restored by the intervention of Nepalese Gurkha and Southern Indian troops, who were less given to the sectarian passions of the northerners. The assassination of Gandhi by a right wing Hindu also caused some pause to the likes of Patel and the rest of the nation who perhaps only then began to glimpse the lunacy that their sectarianism was bringing.

Hajari is particularly interested in the origins of Pakistan’s current disfunction and sponsorship of terrorism, something which he shows very well. However the book also casts significant light on the current disfunctionalities of the Indian state.

Shortly before the victory for Prime Minister Modi’s BJP in the Indian general election I spoke to an Indian friend about the anticipated result. He argued that there were three strands in the Indian independence movement: the Nehruist/Ambedkarist republican tradition which has been dominant for much of Indian history; a communist/socialist strand which has enjoyed power in some of the Indian states; and finally the Hindu Nationalist tradition which Modi was now bringing to power.

However from Hajari’s account this Hindu Nationalist tradition was a very dominant one in the first Indian government, constantly undermining the visions of Nehru and Ambedkar. The caste-based apartheid, the rapes and murders of girls and young women, the enslavement of vulnerable workers that disfigure contemporary India, the world’s largest democracy, may, at least in part, be seen to derive directly from the Hindu-nationalist vision that so bloodily asserted itself in 1947 and asserts itself still to the present day.

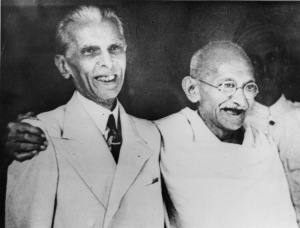

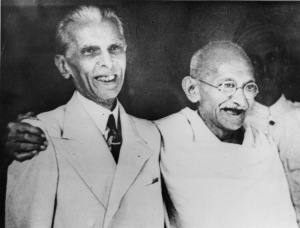

Gandhi and Jinnah in happier days

Midnight’s Furies is a beautifully written but harrowing account of the origins of India and Pakistan. It is an important book about the origins of a contemporary Cold War, about human beings’ inhumanity to other human beings, about how magnaminty and empathy are so vital to diplomacy, and how their absence can lead to carnage.

Ah Spenser! We have been too long apart!

Ah Spenser! We have been too long apart!