Summary: A gripping and insightful account of leadership in the days when the world almost came to an end.

Summary: A gripping and insightful account of leadership in the days when the world almost came to an end.

Thirteen Days is Bobby Kennedy‘s memoir of the Cuban missiles crisis. It was incomplete at the time of his assassination and yet remains an arrestingly insightful work.

Bobby played a crucial role in the Cuban missiles crisis, being one of a minority of “doves” on the “ExComm” drawn together from the highest echelons of the government and military to advise the President. It was in no small part because of Bobby’s advocacy that the “doves” on ExComm won the crucial arguments to set the US strategy in relation to the crisis.

But, while being straightforward about his role, he sought in no way to present himself as the hero of the book. Rather this role is reserved for his brother Jack, the President.

In an introduction to the book Arthur Schlesinger, Jr notes that Bobby Kennedy once commented “The 10 or 12 people who had participated in all these [ExComm] discussions were bright and energetic people. We had perhaps amongst the most able in the country and if any one of half a dozen of them were President the world would have been very likely plunged into catastrophic war.”

That the world did not get plunged into such a catastrophic war is in large part a measure of the extraordinary calmness of Jack in his deliberations and, above all, his startling moral courage in being prepared to face down his military advisers who wanted to bomb Cuba and invade as first response to the discovery of the missile sites. Bobby commented on their attitude in the book, “I thought, as I listened, of the many times I had heard the military take positions which, if wrong, had the advantage that no one would be around at the end to know.” Afterwards Jack told his friend Ben Bradlee, the legendary Washington Post editor, “The first advice I’m going to give my successor is to watch the generals and to avoid the feeling that because they were military men their opinions on military matters were worth a damn”.

It’s good advice not just for a political leader dealing with the military but also for one dealing with any professional group, particularly police and security forces, and indeed for any leader dealing with those claiming “expert” knowledge. A key theme of the book is the importance of debate and disagreement in decision making, as a process of obtaining the best options to even the most horrendous challenge and avoiding the sort of “groupthink” that can lead one unquestioningly towards stupid and undesirable choices.

Reading this book as the carnage of the 2014 war in Gaza seems to have begun again, it is striking how, in spite of being faced with a genuine existential threat to their country and the world, as opposed to the substantially imaginary one posed by Hamas to Israel currently, Jack and Bobby were hugely concerned with the thought of inflicting casualties.Listening to military proposals for a sneak attack on Cuba, Bobby passed a note to his brother, “I now know how Tojo felt when he was planning Pearl Harbour.” Both knew that bloodshed would lead to the situation spiralling out of control, and Jack and Bobby were both familiar enough with the military, and with the human consequences of war,to take this matter lightly. They knew that the lives of untold millions who had neither voted for them nor even heard of them depended on their decisions. So they weighed carefully the consequences of every choice, both immediate and long term. Jack in particular was always striving to empathise with Khrushchev’s position and to give him ways in which he also could exit the quagmire in which they found themselves. Ultimately Jack, again displaying enormous moral courage, took the considerable political risk of instructing Bobby to make a secret offer of withdrawing Nato missiles in Turkey in exchange for the Soviet withdrawal of their missiles from Cuba.

Aside from the drama of the story the book is teeming with insights on war, politics, decision making, and the moral courage that is fundamental to leadership, and filled with vivid scenes: after the crisis is passed, Jack remains in his office is sitting at his desk writing a letter to the widow of the American pilot killed in the course of the crisis.

Arthur Schlesinger, Jr called the book a minor classic. He was right. It’s a short but extraordinary work that will bear rereading.

Whoops! is a clear, cogent and coherent explication of how the financial crisis came about, emerging from a culture of greed and a ludicrous, supposedly rational, belief that risk could, for all intents and purposes, be eliminated from financial transactions. More frightening is that almost nothing has been done to prevent such a crisis happening again – President Obama’s modest efforts having been eviscerated by the right of his own party and nothing notable in Europe at the time of publication in 2010.

Whoops! is a clear, cogent and coherent explication of how the financial crisis came about, emerging from a culture of greed and a ludicrous, supposedly rational, belief that risk could, for all intents and purposes, be eliminated from financial transactions. More frightening is that almost nothing has been done to prevent such a crisis happening again – President Obama’s modest efforts having been eviscerated by the right of his own party and nothing notable in Europe at the time of publication in 2010.

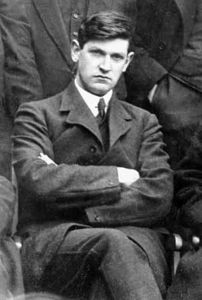

Margery Forester’s “Michael Collins: The Lost Leader” was generally regarded as the definitive biography of Collins until

Margery Forester’s “Michael Collins: The Lost Leader” was generally regarded as the definitive biography of Collins until