There is much international human rights law in the world, and in its midst there is a significant body of law on slavery.

But in spite of all this slavery is still widespread across the world. This is so for a number of reasons. First slavery is still in many places legal.

It is effectively legal in Saudi Arabia. In Qatar and United Arab Emirates the Kafalah system provides a legal underpinning for the enslavement by migrant workers by private individuals. In Uzbekistan and Tajikistan state-sponsored forced labour, particular in the cotton harvest, is used for the enrichment of the elites. In the United Kingdom trafficking of overseas domestic workers has de facto been legalised.

Slavery is also deeply institutionalised in North Korea, and as with Uzbekistan and  Tajikistan, it is used to sustain the privilege and power of that country’s elite.

Tajikistan, it is used to sustain the privilege and power of that country’s elite.

But, while the world often sees North Korea as an isolated place, consideration of the issue of North Korean slavery shows that it is not nearly so much an isolated thing.

The 2015 United States Trafficking in Persons report notes that, “Chinese authorities continued to forcibly repatriate some North Korean refugees by treating them as illegal economic migrants, despite reports some North Korean female refugees in China were trafficking victims. The government detained and deported such refugees to North Korea, where they may face severe punishment, even death, including in North Korean forced labor camps. The Chinese government did not provide North Korean trafficking victims with legal alternatives to repatriation. The government continued to bar [United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees] access to North Koreans in northeast China; the lack of access to UNHCR assistance and forced repatriation by Chinese authorities left North Koreans vulnerable to traffickers. Chinese authorities sometimes detained and prosecuted citizens who assisted North Korean refugees and trafficking victims, as well as those who facilitated illegal border crossings”.

All of this is contrary to China’s obligations to protect victims of trafficking under the Palermo Protocol of which they are a signatory. China’s failure provides means for Chinese traffickers to coerce their victims with the threat of denunciation to the Chinese authorities. It further sustains the institutional practices of slavery in which North Korea indulges, by effectively enforcing North Korea’s policies beyond its borders.

I would caution the rest of the world from getting too judgemental about this too quickly though. Here we see China indulging in something that the rest of the world also does: erasing an inconvenient slavery problem by the simple assertion, made with great conviction, that it is not actually a problem of slavery. Suggest to any Home Office minister or official that the UK’s overseas domestic worker visa is a license to traffick, and you will see this process in action here.

And of course the complicity with North Korean slavery is not restricted to China. In November 2014 the journalist Pete Pattisson exposed in the Guardian how North Korea trafficked construction workers to Qatar for work on the diverse building projects there.

As I noted at the outset Qatar has legal mechanisms in place to facilitate the enslavement of vulnerable workers by private individuals. One of the consequences of this is that the 2022 World Cup is likely to be the bloodiest sporting event since Julius Caesar’s funeral games. That fact has not caused the repudiation of Qatar in any international forums.

What Pete’s journalism exposed however is one of the sources of hard currency that props up the North Korean dictatorship is from North Korea’s sale of its people internationally. And that again has not caused any sort of repudiation of Qatar or those countries which also avail of the cheap labour of trafficked North Koreans. In October 2015 the UN Special Rapportuer on Human Rights in North Korea estimates that 50,000 North Korean workers are employed in foreign countries, mainly in the mining, logging, textile and construction industries and that the number is rising.

The UN Special Rapporteur estimated that the vast majority are working in China and Russia but others are reportedly employed in countries including Algeria, Angola, Cambodia, Equatorial Guinea, Ethiopia, Kuwait, Libya, Malaysia, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nigeria, Oman, Poland, United Arab Emirates and, of course, Qatar. If North Korea obtains only $10,000 per worker per annum this traffick in human beings would be worth half a billion annually to the dictatorship.

A fundamental issue that we see in many slavery cases, and exemplified in relation to North Korea, is that it is an international issue and needs therefore to be tackled internationally. The importance of international law, and international rule of law is exemplified in relation to North Korea. I suspect that like the UK China’s equivalent of the ministerial code has no mention of international law and so ministers considering their policy in relation to North Korean refugees and victims of trafficking are able to lightly dismiss their human rights obligations and those under the Palermo protocol.

The case of North Korea also shows that slavery must become a central issue of diplomacy. The easy acquiescence that the international community has in the slavery practices of other countries, aside from its moral bankruptcy, is also now a security risk. If the North Korean elite were not obtaining hard currency from the international trafficking of its citizens it would be that much more difficult for the dictatorship to cling to power.

I wonder do many consumers consider the risk of North Korean forced labour in garments that they purchase from China. Whether they do or not again the issue of the enslavement of North Korean exposes the need for new international law. Franklin Roosevelt effectively ended child labour in the United States by banning its use in inter-state commerce. President Obama has taken a leaf from Roosevelt’s book in introducing powers to exclude slavery tainted sea-food from the US.

The European Union should follow suite and establish similar general powers that could be used against the import or any goods manufactured with the use of forced labour, including that for trafficked North Koreans. Such a measure would have repercussions through the entire global political economy by causing real economic threat to those countries that have come to routinely use forced labour of vulnerable workers.

We see much that is horrible and distressing when we look at the institutions of slavery in North Korea, including our own reflection: that of the rest of the world at best standing idly by, at worst benefiting.

That needs to come to an end, not merely with fine words, but with robust and clear sighted international action. I hope the UK, for as long as it is part of Europe, will begin to provide proper leadership on this and bring the authority of the world’s largest single market to bear on this vital human rights issue.

The Protestant victims of the IRA’s Kingsmill massacre also showed a impressive anti-sectarian heroism as they tried to protect their Catholic colleagues from what they initially thought was a similar UDR/UVF attack, before the horrendous realisation that the war criminals in question on this occasion had come to butcher them.

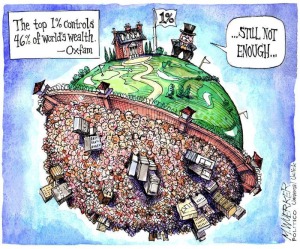

The Protestant victims of the IRA’s Kingsmill massacre also showed a impressive anti-sectarian heroism as they tried to protect their Catholic colleagues from what they initially thought was a similar UDR/UVF attack, before the horrendous realisation that the war criminals in question on this occasion had come to butcher them. I don’t agree with this perspective but my opinion will make little difference when weighed against the vast piles of loot that wholly legal tax avoidance could deliver. In any event that shouldn’t matter. The potential for tension and conflicts between competing moral philosophies was something which Adam Smith already anticipated in The Wealth of Nations (1776) when he argued that it was the state’s responsibility to regulate businesses: how companies can be made to make fair tax contributions is among the most pressing issues of business regulation today.

I don’t agree with this perspective but my opinion will make little difference when weighed against the vast piles of loot that wholly legal tax avoidance could deliver. In any event that shouldn’t matter. The potential for tension and conflicts between competing moral philosophies was something which Adam Smith already anticipated in The Wealth of Nations (1776) when he argued that it was the state’s responsibility to regulate businesses: how companies can be made to make fair tax contributions is among the most pressing issues of business regulation today. This week,

This week,