Summary: Photos from 2022

Summary: Photos from 2022

Summary: some humanitarian assistance for book shopping this Christmas

As Christmas approaches some of you may be pondering books for yourselves or the bibliophiles in your life.

So here, in (more or less) chronological order are my best books of the year. Four entries are Irish; three about aspects of the British empire and one is about an aspect of the American empire; two trace the roots of Israel’s genocide in Palestine; two are feminist dystopian thrillers and one is a bit of feminist literary criticism; and there is one that is about pretty much everything. And there is some stuff about the Roman Empire, because there sorta has to be.

Each item has a link to a longer review if you want to know more. Hopefully some will supply some of you with some inspiration.

That makes 13. A lucky number.

Summary: I would be more forgiving of this book if there had been more about Bridie and Donal in it.

I worked with a lot of Irish nurses in Ethiopia and Angola. They were a tough, sexy bunch, ruthlessly professional and deeply committed to social justice. (The character of Sophia in my novels The Undiscovered Country and Some Service to the State was modeled in no small part on some of them.)

As a professional group, certainly as an Irish professional group, they have probably done more than any others to make the world a better place.

I imagine Bridie Gargan must have been quite like them. A 27 year old in 1982 she was already making the world a better place working as a nurse. Having just finished a long shift one day she decided to reward herself on her way home with a spot of sunbathing in Dublin’s Phoenix Park. It was there she had the misfortune of encountering Malcolm Macarthur, who proceeded to beat her to death with a hammer.

After Bridie, Macarthur went on to kill Donal Dunne, a farmer, with his own shotgun. It seems that these killings were part of a half-baked plan that he had to commit an armed robbery to replenish his finances after he had squandered an inheritance. Macarthur was such a wastrel that he simply could not contemplate working for a living.

Having finished it, I am left with very mixed feelings about A Thread of Violence, Mark O’Connell’s account of a protracted series of meetings that he had with Macarthur following his release on licence for the murders of Bridie and Donal. O’Connell had set himself the task of trying to get to the bottom of what motivated Macarthur to such grotesque violence.

It is a beautifully written book, and it is important, I believe, to try to understand violence to better prevent it. But in the end O’Connell adds little illumination to these dreadful events and he admits that he never did get to the bottom of the question of motivation.

So, what justifies this literary treatment of Macarthur, a worthless man who has led a worse than worthless life? I am left feeling not much, particularly as O’Connell writes so little about Bridie and Donal who barely feature in this book other than as victims. O’Connell missed the opportunity, in my view, to show how these much more consequential people deserve more attention than their self-important killer.

I can understand how O’Connell, as a working writer doubtless with a contract to fulfil, must have felt he had to write something in spite of his admitted failure to achieve his aim. But I am sad to say that I do not think this book adds much to human understanding.

Summary: books that it would be criminal to overlook!

I once met a woman who had given her newborn daughter the second name of “Danger” just so when she was older she would be able to say, like the heroine of a 1930s movie, “Danger is my middle name!”,

There is a strong hint of such movie heroines in Lauren, the investigative journalist protagonist of Louise Minchin’s Isolation Island.

Minchin uses her experience of journalism and having been a contestant on the storm ravaged set of “I’m a Celebrity, get me out of here!” to craft a fun, Agatha Christie inspired, tale of murder amongst game show contestants.

Minchin brings a lovely devilment to her tale, fattening up the despicable before despatching them while Lauren desperately tries to unearth the evil genius behind the mayhem.

Minchin has described her heroine as being braver than herself. That may or may not be true – Minchin is also a triathlete and having done one myself I can attest that those are daunting things. But, perhaps as importantly Lauren is driven by a sense of journalistic ethics and a conviction of the importance of truth, which must be Minchin’s own.

In a time of in which even genocide is being made undiscussable, it is important to be reminded that some truths, no matter how inconvenient, must be spoken.

On the opening page of The Trials of Lila Dalton, the titular Lila, a barrister it seems, stands up in court with no knowledge of how she got there, but with a client to defend. LJ Shepherd, the author, a barrister herself, describes her book as an “ontological mystery”. That is, not only does her protagonist have to get to the bottom of the facts of her case – the defence of a man accused of a bombing atrocity – but also work out who the hell she is and what she is doing there.

Shepherd’s is an entertaining and intriguing story. I am not sure that it really required the reality questioning elements as the issues she deals with – the importance of the right to a defence in a criminal trial no matter how seemingly heinous the accused, and the question of how democratic societies protect themselves from violent assaults by those who do not share their values – are important enough.

These quibbles aside, the quality of Shepherd’s writing is exceptional, particularly when describing the treating of casualties in the aftermath of an explosion: these recalled for me some of the accounts of the survivors of the Rana Plaza collapse in Bangladesh. In this Shepherd does that most difficult of things: she forces the reader to empathise with victims that they may prefer not to think of.

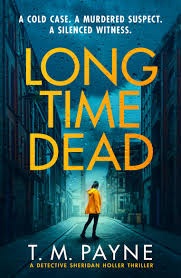

In Long Time Dead, an extra body shows up in a grave and it is identified as a man suspected of murdering a cop and grievously injuring a bystander seven years earlier. The investigation eventually falls to Detective Inspector Sheridan Holler.

It was Chandler, I think, who conceived of his tales of gumshoes as updated versions of the stories of Knights Errant from Arthurian legend. So, whatever else was unclear in his mysteries, no matter how corrupt the world in which they ventured, one thing you could count on was that his shamus would endeavour to do the right thing, protecting the innocent and unmasking the guilty.

TM Payne’s peeler protagonist in Long Time Dead is an inheritor of that tradition. While she may find the sort of defence barrister of which LJ Shepherd writes somewhat distasteful, she is still fundamentally decent and committed to the finding the truth.

There is an echo of Payne’s book in Catriona King’s A Limited Justice. Like it, it is a police procedural – a type of crime novel for which I have a particular affection.

Both have the bonus of being written by writers who know what they are talking about: Payne is a former cop; King has worked as a police forensic medical examiner. Both eschew the brooding detective for sympathetic professionals – the sort of people who you might actually like to work with.

A Limited Justice begins with King’s investigator, Marco Craig, opening a probe into a particularly grisly killing on a Belfast garage forecourt. As with many of the Sherlock Holmes stories, as the investigation unfolds the story of the perpetrator and their motivation becomes as important as that of the investigators. Consequently, King is able to use her story to explore not just the crime itself, but contemporary Northern Ireland. As is typical of Northern Ireland the story is replete with black humour.

Both King and Payne have founded book series based on their protagonists. It is easy to see why: both are appealing companions on the mean streets of the imagination, and King and Payne, like Minchin and Shepherd, are both very gifted writers.