Summary: the colours of the rainbow, so pretty in the sky, are also on the faces of the places you go by…

Summary: the colours of the rainbow, so pretty in the sky, are also on the faces of the places you go by…

Summary: American Hastings Banda

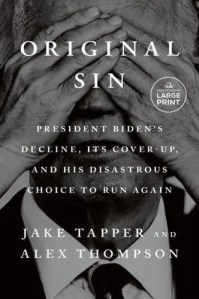

On a human level, this book is a very sad one. Across it, informants repeatedly refer to how their encounters with Joe Biden in the later stages of his presidency reminded them of their own impaired elderly relatives. Indeed, the descriptions of Biden’s deterioration within this book reminded me more than once of my father’s decline.

Of course, devastating as that was, I can be confident that no matter how afflicted my father became, unlike Biden, he would never have added his support to a genocide.

I counted four references to the violence in Palestine across this book, starting with a brief mention of the Hamas atrocity on 7 October 2023, and ending with another brief mention that Biden’s Gaza policy was the area of most substantial disagreement, in private, between Biden and his Vice President Kamala Harris.

This lack of discussion of one of the great moral issues of our day is, perhaps, unsurprising. Tapper and Thompson’s interests, like those of most Americans, are wholly US-centric. For them American preoccupations are paramount. And so they focus on the threat to American democracy posed by Biden’s cogitative decline and the opportunities that this gave to a resurgent Trump. They are uninterested in consequences of the moral collapse in international affairs of Biden and the swathes of the US political establishment that were their sources for this book. That doesn’t directly affect Americans.

This is somewhat disingenuous. There are occasional references through the book to Biden’s loss of support amongst young people. This is attributed solely to Biden’s age. Tapper and Thompson do not consider the possibility that abject disgust at Biden’s support for a racist and genocidal government in Israel could have deprived Harris of the small margins she needed in key battleground states to keep the presidency out of Trump’s hands.

In many respects Original Sin is a fine work of investigative reporting, and it does give important insight into the nature of power in the United States: Biden’s presidency gave power to a small cadre of advisers around him known, behind their backs at least, as the Politbureau. It was in this group’s selfish interest to deny to the world the fact that Biden was no longer physically or mentally fit to be president. To have done otherwise would have been a surrender of the power that they craved.

But the authors’ disinterest in the most murderous of Biden’s policies is reflective of one of the two original sins of the United States: that it was built on genocide and that many in the highest echelons of government still seem to regard this as a legitimate policy option. As a republic it has never quite grasped that human rights are meant to be universal.

Given this, it is difficult sometimes not to feel that in some grand Karmic way the United States deserves Trump: they reap now for themselves what they sowed so long for others.

Summary: an elegant exploration of Hiberno-Indian relations over the decades

While anti-colonialism is now deeply culturally embedded in contemporary Ireland, our history on the matter, as Cauvery Madhavan gently reminds us with this book, is rather more complicated.

The Tainted takes as its starting point a fictionalized story of a 1920 mutiny by Irish troops in India. (In the book the “Kildare” rather than the Connaught Rangers are the mutineers).

Because, superficially, the British and Irish are white, the British expect the Irish to collaborate with them in treating the Indians in the way that the British treat the Irish at home.

By and large the Irish are happy to comply. But when news of the depredations of the Black and Tans percolates through to the Irish barracks the centre cannot hold, and the colonial authorities are murderously provoked when Irish soldiers down arms in protest.

The second two-thirds of the book explore the repercussions from this incident down the years, not least for Rose, a young “Anglo-Indian” woman – daughter of an Irish father and an Indian mother.

Cleverly Madhavan does not allow her narrative to rest with any single character for too long. Instead she shifts the psychological perspective of the novel across a range of characters into the first decades of Indian independence. By doing this she gives insight into the attitudes and prejudices of different communities, and shows how these pose needless challenges to the appreciation of each other’s common humanity.

Madhavan’s novel is an engaging and illuminating exploration of identity, cultures and history, elegantly written and ultimately hopeful. After all, whatever our skin, our blood is the same colour.