When We Were Kings, by Leon Gast

The Ghosts of Manila: The Fateful Blood Feud Between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier, by Mark Kram

The Tao of Muhammed Ali, by Davis Miller

My first proper memory of Muhammed Ali was waking up to the news of his victory over George Foreman in Kinshasa in 1974. I watched the BBC Sports film of the fight the next evening. It was awe-inspiring.

My first proper memory of Muhammed Ali was waking up to the news of his victory over George Foreman in Kinshasa in 1974. I watched the BBC Sports film of the fight the next evening. It was awe-inspiring.

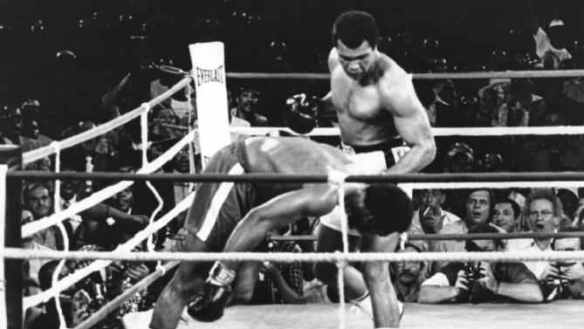

This fight is the principle subject of Leon Gast’s electrifying documentary When We Were Kings. The bloody, thieving, murderous dictator of Zaire, Mobuto, had decided that the world heavyweight title fight would help put Zaire on the world stage. Gast’s movie is an account of the extraordinary circus that resulted. It intercuts documentary and news footage from the time with illuminating interviews with, among others, George Plimpton and Norman Mailer, on the bizarre circumstances surrounding the fight, and on the phenomenal fight itself.

When We Were Kings is a great introduction to Ali, both as a cultural and political figure and as a boxer. His victory is beautifully explained as one not just of his technical fighting skills, but of his strategic thinking skills.

Rope-a-dope

Years later George Foreman described the devastation of having been beaten by someone so “braggadocio”. This is but a hint of the darkness that is frequently ignored in discussions of Ali. This comes much more to the fore in the Ghosts of Manila, an account of the rivalry between Ali and the great Joe Frazier. Frazier had been a supporter of Ali in the wilderness years when Ali had been stripped of his licence to box because of his courageous refusal to fight in Vietnam: “I ain’t got not quarrel with the Viet Cong. No Vietnamese ever called me nigger!” he said by way of explanation.

However this was no protection to Frazier from Ali’s often cruel and lacerating invective. Frazier came to detest Ali and their brutal fight in Manila in 1975 has become a thing of legend.

Manila

Both fighters inflicted incredible damage on each other in dreadful heat, displaying incredible levels of endurance and courage just to keep up with each other. However by Kram’s account Frazier had effectively won the fight by rendering Ali unable to take the ring for the 15th and final round. All Frazier needed to do was to stand up. Then his manager, without consulting Frazier, threw in the towel, appalled at the damage that Frazier himself had already sustained in the fight. Frazier never forgave his manager and this extraordinary stroke of luck for Ali became a fundamental element in his legend.

But brutal fights such as Manila and the necessity to fight on almost to middle age that resulted from the loss of his license in his peak years, took their toll on Ali’s body and resulted in the Parkinson’s Disease that afflicted his final years. Davis Miller had met Ali at the peak of his career but became friends with him in these years. The Tao of Mohammed Ali is about a number of things including this friendship, writing, boxing, and perhaps most poignantly about Miller’s relationship with his own father. It is a fine and moving book that describes beautifully what Ali meant to ordinary fans, millions of who are today bereft at the news of his death.

The world is a duller, smaller place with Ali gone. But in many ways it is a better one in part because of what he did and what he stood up for. We will never see his like again.

Ali delivers the coup de grace on Foreman (Plimpton and Mailer look on – bottom right)

Agnes Magnusdottir has been condemned to death for her involvement in the murder of two men, one of them her lover. As she awaits confirmation of her sentence she recounts the events leading up to these deaths to a young priest, appointed as her spiritual advisor, and the members of the family she has been billeted with.

Agnes Magnusdottir has been condemned to death for her involvement in the murder of two men, one of them her lover. As she awaits confirmation of her sentence she recounts the events leading up to these deaths to a young priest, appointed as her spiritual advisor, and the members of the family she has been billeted with.

On Easter Monday, 24th April, 1916, a group of armed Irish rebels occupied the General Post Office (GPO) and other major buildings across the city of Dublin. It was the beginning of the Irish War of Independence that would last with varying degrees of political and military intensity until 1921.

On Easter Monday, 24th April, 1916, a group of armed Irish rebels occupied the General Post Office (GPO) and other major buildings across the city of Dublin. It was the beginning of the Irish War of Independence that would last with varying degrees of political and military intensity until 1921.

After six days it was over, crushed by the might of the British Empire that overwhelmed them with troops and heavy guns. The O’Rahilly, despite his opposition to the rebellion, ultimately felt duty bound to participate, and was killed towards the end leading an attack on a British machine gun position to give cover to the withdrawal from the GPO. As The O’Rahilly himself had put it in a phrase later taken up by Yeats, the man who had helped wind the clock came to hear it strike.

After six days it was over, crushed by the might of the British Empire that overwhelmed them with troops and heavy guns. The O’Rahilly, despite his opposition to the rebellion, ultimately felt duty bound to participate, and was killed towards the end leading an attack on a British machine gun position to give cover to the withdrawal from the GPO. As The O’Rahilly himself had put it in a phrase later taken up by Yeats, the man who had helped wind the clock came to hear it strike. By the standards of the First World War this was a trifling affair. In the blood bath of the Somme that would begin a few weeks later thousands of Irishmen, nationalist and unionist alike, were pointlessly butchered alongside English, Scots, and Welsh, in the name of Empire.

By the standards of the First World War this was a trifling affair. In the blood bath of the Somme that would begin a few weeks later thousands of Irishmen, nationalist and unionist alike, were pointlessly butchered alongside English, Scots, and Welsh, in the name of Empire.

The Protestant victims of the IRA’s Kingsmill massacre also showed a impressive anti-sectarian heroism as they tried to protect their Catholic colleagues from what they initially thought was a similar UDR/UVF attack, before the horrendous realisation that the war criminals in question on this occasion had come to butcher them.

The Protestant victims of the IRA’s Kingsmill massacre also showed a impressive anti-sectarian heroism as they tried to protect their Catholic colleagues from what they initially thought was a similar UDR/UVF attack, before the horrendous realisation that the war criminals in question on this occasion had come to butcher them.