Speech to 2014 Annual General Meeting of Dalit Solidarity Network

I started my professional career as a water engineer and spent years in Ethiopia, Eritrea, Afghanistan and Angola focused on how water and sanitation interventions could help reduce poverty or mitigate the consequence of war.

There are millions of people alive today across the world because of the work of water and sanitation engineers and this work remains a vital, under-resourced and often under-appreciated strategy in long term poverty reduction and humanitarian response.

Badaun sisters’ rape-murders: ‘They could have been saved if police acted’, says family

But it’s not a panacea. And I was appalled last week to read an article on the BBC website, which presented seriously the idea that a new latrines programme in the Indian village of the two young girls found hanged in a tree in May, after they had gone to defecate in the open, was a sufficient response to their rape and murder.

The founder of the charity that put the new latrines into the village declared that “I believe no woman must lose her life just because she has to go out to defecate”, echoing Prime Minister Modi’s Independence Day speech on 15 August when he vowed to end open defecation.

“We are in the 21st Century and yet there is still no dignity for women as they have to go out in the open to defecate and they have to wait for darkness to fall,” he said. “Can you imagine the number of problems they have to face because of this?” he asked.

Open defecation was a problem in Angola, Ethiopia and Afghanistan when I worked there but while poor sanitation is a constraint particularly on girls education and renders millions of women vulnerable to all forms of sexual harassment and assault, it does not inevitably lead to an epidemic of rape and lynchings. Other factors are necessary for that to occur.

Anybody brought up with the Rockford Files knows that all crimes, particularly murders, have three fundamental elements: motive, means and opportunity. But starting with an article in the Guardian by the director of Wateraid shortly after these atrocities there has been a tendency amongst some leaders to substitute the motive for these rape-murders with the opportunity for them.

I would like to discuss why this has been happening because I feel it touches upon an important and troubling issue.

The American business theorist Chris Argyris identified the issue of “undiscussability” as a key factor in reducing the capacity of organizations and businesses to perform effectively. Organizations, he found, were unable to discuss risky or threatening issues especially if these issues question the underlying assumptions and policies of the organization.

That idea applies to states and communities as well as organizations. And so responses to the deaths of these two girls have avoided perhaps the most undiscussable issue in human history: that of the intrinsic violence of caste-based apartheid.

Arundhati Roy points out in The Doctor and the Saint that, “Poverty … is not just a question of having no money or no possessions, Poverty is about having no power”. Caste-based apartheid maintains that exclusion from power of hundreds of millions of citizens in a way that is vitally important politically and economically for powerful elements of society’s elites.

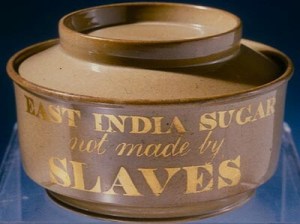

It is increasingly clear for example that the maintenance of this social system provides competitive advantage to South Asia, particularly India, in the globalising political economy. Caste-based apartheid underpins the “camp coolie” and “Sumangali” systems allowing the powerful to enslave with impunity vulnerable workers, often young Dalit women and girls, and hence to derive considerable profits from their enslavement. Each of us in this room is also benefiting from that enslavement as it allows, amongst other things, the provision of cheap clothes to our high streets and so, each of us is probably clad in at least one garment that has been produced in some part through the labour of enslaved people.

Making the issue of caste-based apartheid undiscussable insulates it politically and allows the elite greater security in their feudal level of aristocratic privilege: how can something become a political issue if one cannot even give voice to the question?

So I suppose I should not be shocked that a response to the rape-murder of two young Dalits is a sanitation programme. It comes from the same philosophical tradition as a compulsory education law to address child labour or a rural employment guarantee scheme to respond to bonded adult labour.

Each of these programmes hopes to treat a serious symptom of poverty, and indeed they do hold potential to do so. But they scrupulously avoid mentioning the cause of the problems. That is because the cause of the problems is caste-based apartheid and the child labour and slavery that this facilitates and there are too many vested interests who benefit from that for it to be a politically safe topic of conversation.

The failure to engage with the undiscussable issue of caste in South Asian society is a failure in the most basic principles of good development practice. There has been over the past decade a growing discourse of development as a technocratic project. That is an idea that poverty reduction is principally about the transfer of things to people who do not have things. Bill Gates has been a particularly powerful advocate of this approach and we see it reflected in, for example, Fairtrade’s fixation on prices paid to producers as the holy grail of poverty alleviation, to the exclusion of almost all other development issues.

But effective democratic development is not primarily a technocratic, or even an economic, challenge. It is a political one. Democratic community development should be about empowerment of vulnerable and at risk people. Sometimes the constraints on empowerment are material things. But much more often they are social systems which aim to exclude certain people from inclusion in society and in poverty reduction measures, and if these are unaddressed by development processes then the development project itself is constructed on foundations of sand. Dr Ambedkar’s words in relation to just revolution also pertain to just development: “What is required is a profound and thorough conviction of the justice, necessity and importance of political and social rights”.

But the challenge of caste-based apartheid and its undiscussability shows something more profound. Development is also a philosophical project: it is about finding the cause of injustice and calling it by its true name. Without this the system retains its power to warp and undermine even the most well-meaning efforts towards justice.

When I was thinking about what I was going to say here Seamus Heaney’s words from his poem “Whatever you say, say nothing” kept coming back to me:

O land of password, handgrip, wink and nod,

Of open minds as open as a trap,

The outside world does not well understand the South Asian codes for caste discrimination allowing the perpetrators greater leeway to continue with what they are doing guarded by silence, and by this incomprehension, from criticism by the international community. And the enforced silence around caste-based apartheid now extends as far as the UK with this British government’s pusillanimous acquiescence to Brahminist lobbying by refusing fundamental protections of British law to British citizens who happen to be Dalits.

And so the trap of caste-based apartheid that has ensnared millions of people across the world still grips, and its grip threatens fundamentally the democracy of those states that tolerate it, not least the world’s largest democracy.

Heaney went on to describe the explosive potential that injustice stoked in oppressed communities. That explosive potential must also exist in contemporary India and the rest of South Asia so long as the violence of caste-based apartheid is unaddressed. There remains time to prevent conflagration by acting with justice. As Ambedkar pointed out “Law and order are the medicine of the body politic and when the body politic gets sick medicine must be administered“. Specifically effective rule of law across South Asia must be extended by expansion of the judiciary, rooting out of corruption in the police, criminalisation of caste discrimination and making sure that laws like the Indian rural employment guarantee scheme and compulsory education act are fully and effectively implemented.

But time is running out. And if the rest of us remain silent on this issue of caste-based apartheid then we will also have to accept some measure of responsibility next time we hear of other crucified Dalits hanging from trees.