Summary: calls for humanitarian aid are being used by pusillanimous politicians to distract from their failures to directly address the causes of humanitarian crisis in Gaza, most specifically Israel’s genocidal assault.

For over five years in the late 1990s I worked, mostly for Oxfam GB, organizing assistance, including water supply and sanitation, for the civilian victims of the civil war in Angola.

So, humanitarian response is a subject area I know a little about. As students of management and leadership will be aware, a problem with a bit of expertise is that you can presume that everyone understands the fundamentals as well as you do. This is called taken-for-grantedness in the literature.

I have been taking-for-granted that David Lammy and Keir Starmer – human rights lawyers after all, as they like to tell us, and therefore smarter than everyone else, as they like to imply – would understand the fundamentals of humanitarianism. After all, they have been pontificating on it since the start of Israel’s murderous assault on Gaza in 2023.

But maybe they don’t. Maybe it is possible that they are not the craven accomplices to war crimes that their ongoing military and diplomatic support of Israel suggests. Perhaps they are just pig ignorant of the vitally important stuff that successful humanitarian response requires.

So, here are a couple of the most basic lessons of humanitarianism for their edification.

1. The solution to a humanitarian crisis caused by war is not aid. It is an end to war. At the early stages of Israel’s latest assault on Gaza, Starmer and others attempted to deflect from their monstrous acquiesce in Netanyahu’s war crimes by rejecting the calls for an immediate ceasefire and instead calling for pauses in the violence to allow for the delivery of more aid.

The technical term for this position in relation to humanitarian response is “Oxford Union debating horseshite”. It is part of an approach to politics that values a plausible sounding point to win an immediate argument over the concrete measures necessary to resolve the actual causes of the crisis that the argument is about. Food assistance, vital as it is, does not protect from the other forms of collective punishment, such as the cutting of power and water that Keir Starmer advocated Israel doing, let alone the mass burning alive of children that Israel has routinised in Gaza since the outset of its violence.

2. If a belligerent nation is using famine as a weapon of war, then they are not going to permit humanitarian assistance unless put under robust pressure to do so. Robust pressure, not expressions of sadness or concern: Boycotts. Divestments. Sanctions. Criminal accounting.

3. If an assaulting army deliberately massacres humanitarian workers delivering food aid to hungry people, they are probably using famine as a weapon of war. Humanitarian workers not party to that war crime will therefore be made a target.

4. If an assaulting army on encountering their own nationals, stripped to their underpants and begging for help in their own language, shoots them, then that army is not on a rescue mission. Imagine what fate awaits those who cannot speak the attackers language. But you don’t have to because it has been documented by those the Israelis would seek to make victims. Indeed, the Israelis themselves have even videoed their own war crimes to show the world, so proud are they of what they inflict.

5. If an assaulting army is enslaving the civilian population they are attacking, then they are certainly not interested in any aspect of the humanitarian well-being of those civilians. In March 2025 the Israeli newspaper Haaertz reported that, ‘In Gaza, Almost Every IDF [Israeli Defence Forces] Platoon Keeps a Human Shield, a Sub-army of Palestinian Slaves.’

The British government used to like to depict itself as a world leader against slavery. But there has been a deafening silence from that government, and indeed much of the anti-slavery community, on this matter.

6. If you have soldiers in place to machine gun aid recipients, then the purpose of an aid distribution is not humanitarian. It is war crimes.

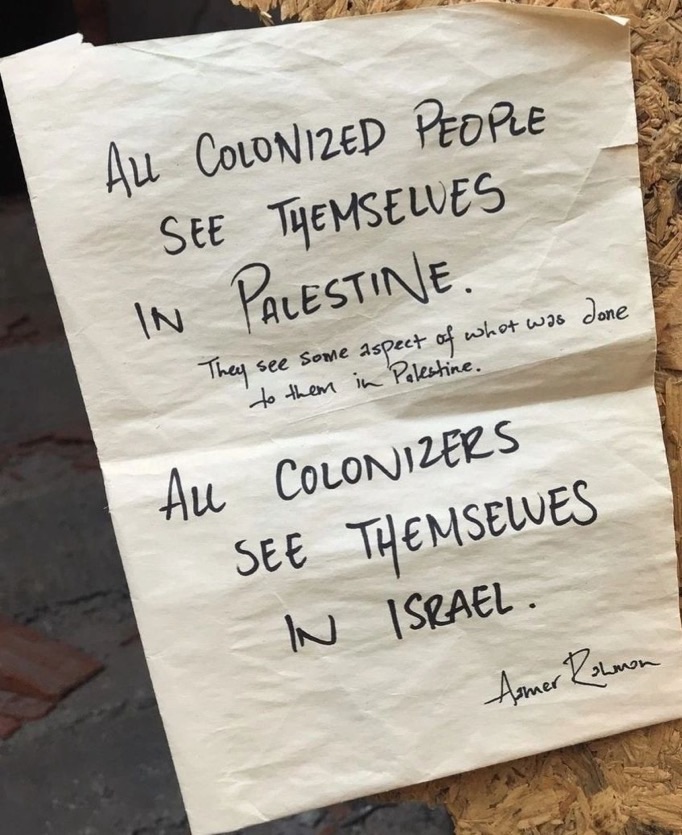

7. If you are materially supporting a political regime that has publicly stated its war aims are ethnic cleansing, then no amount of humanitarian assistance will mitigate that. You too are practicing genocide, even if you are also offering the doomed their meagre last meals.

Maybe these ideas are new to Starmer, Lammy and the rest of their government. But they are not hard. Indeed, tens of thousands of ordinary British people demonstrate that they grasp these most fundamental points already as, month in, month out, they gather in protests across the country to indict their own government for its abject moral collapse.