Summary: the extraordinary first volume of Caro’s planned five volume biography of LBJ

The Path to Power is volume one of Robert Caro’s celebrated, multi-volume biography of

The Path to Power is volume one of Robert Caro’s celebrated, multi-volume biography of

Lyndon Johnson – four volumes have already been published with a fifth planned. This one covers Johnson’s career from birth to the outbreak of the Second World War, including his election to Congress and his first, failed, Senate run.

Nevertheless in spite of its mammoth size this is not a book that I would ever describe as “sprawling”. For all its numerous, fascinating, digressions – into Texas social history or politics, for example, or concise biographies of Sam Johnson, Lyndon’s father, or Sam Rayburn, the powerful Speaker of the US House of Representatives and sometime patron of Lyndon – Caro never once loses sight of the central purpose of his work, which is to try to explain Lyndon Johnson. Hence any digressions that he makes are provided to establish a context from which better understanding can be derived.

Johnson was not a very nice man. But he was a fascinating one with an extraordinary impulse for power, an awesome appetite for hard work, and a fundamental grasp of political campaigning, both for himself and, as described in this book, as a leader of Democratic national election campaigning. (It’s a pity that some of the clowns leading Labour’s disastrous December 2019 election campaign did not spend some time studying this book to learn some of the basics of winning elections.)

In the course of his career he did much good and some extraordinary evil. But he never for a moment seems to have been motivated by anything other than a desire for self promotion. Despite coming from a Texas Liberal tradition – both his father and Rayburn were unequivocal men of the Left, Johnson was not by any means wedded to these ideals. Over the course of his career he shifted from Left to Right and back again depending on the prevailing political winds and which alliances he felt would most probably advance his self interest.

Such calculation was not restricted to his professional life. His marriage to Lady Bird seemed to have been wholly functional, its purpose to obtain for him a rich wife whose family might help bankroll his political campaigns. All of his relationships, with one exception, seem to have been developed with the sole consideration of how they would advance his political career.

The sole exception was his affair with Alice Glass, the wife of one of his most important political backers. Johnson simply could not resist Alice in spite of the damage that it would have caused him had Alice’s husband discovered the true nature of their relationship. Lady Bird had, of course, to live with the humiliating knowledge of the affair, conducted with no concern whatsoever for her feelings.

Alice, in fact, seems to have been the only woman Johnson ever loved. So there is a sort of Karmic justice that towards the end of her life Alice had wanted to destroy all her correspondence with Johnson. She was afraid that her children would discover not that she had an affair, but that she had one with the man most responsible for the US’s murderous involvement in Vietnam.

The Path to Power is a gripping book, elegantly written and displaying an extraordinary depth of research. It is a matter of unspeakable pleasure to know that I have at least three more volumes of this work to read.

The Path to Power is volume one of Robert Caro’s celebrated, multi-volume biography of

The Path to Power is volume one of Robert Caro’s celebrated, multi-volume biography of

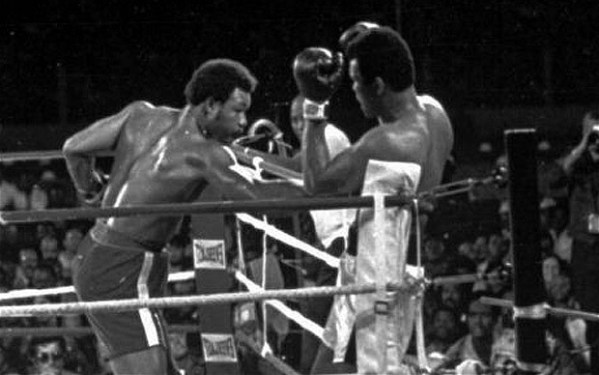

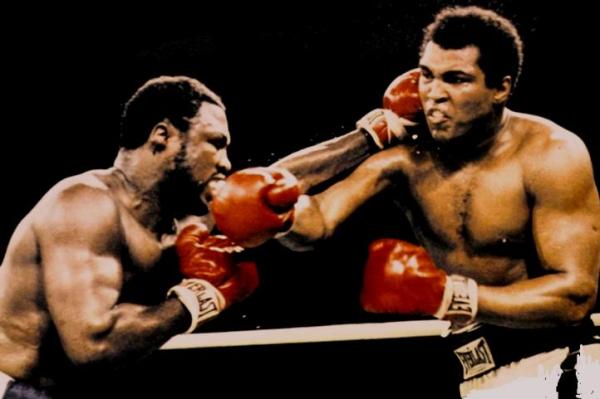

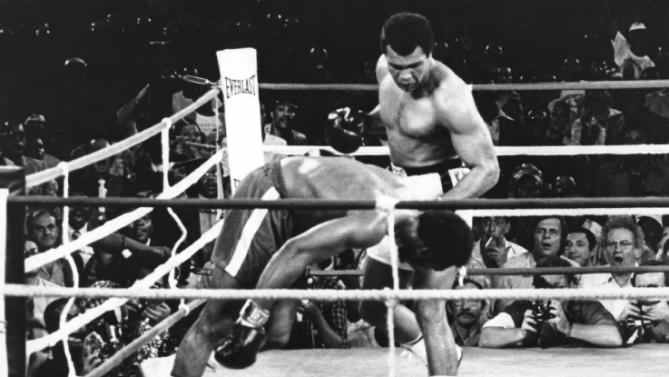

My first proper memory of Muhammed Ali was waking up to the news of his victory over George Foreman in Kinshasa in 1974. I watched the BBC Sports film of the fight the next evening. It was awe-inspiring.

My first proper memory of Muhammed Ali was waking up to the news of his victory over George Foreman in Kinshasa in 1974. I watched the BBC Sports film of the fight the next evening. It was awe-inspiring.