Speech to Westminster event on modern slavery bill and slavery in international supply chains

I would just like to say a few things:

I would just like to say a few things:

First of all I think it is fair to say that the fact that there is a decent bill is a tribute to the work of all the parliamentarians involved who contributed considerable time and effort into moving this bill from its original and narrow law enforcement focus to something that gives greater recognition to the humanity of the victims of the crime and the need to look at what is happening in the supply chains of goods and labour both abroad and in the UK.

It’s a particular privilege to be beside Sir John Randall and Fiona McTaggart today and to have the opportunity to thank both of you for your efforts and those of many other people of moral courage and conviction in the Lords and the Commons who made this possible.

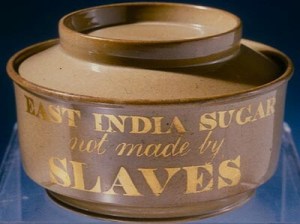

Anti-Slavery has been working on the challenges of ending forced labour in international supply chains for many years, and we have been working for over a year now with parliamentarians, civil society organisation, businesses and lawyers to improve many aspects of the Bill and I would also like to take the opportunity to recognise those involved in ensuring that there is a transparency in supply chains clause in this bill. That there is such a clause is a result of business, trade unions and NGO members of the Ethical Trading Initiative, putting pressure on the government to introduce such a measure to level the playing field of international trade between those who wish to trade more ethically and those who are not bothered.

In truth had businesses not added their voice to this demand there would still be nothing in the bill. Adam Smith believed that it was the duty of states to regulate businesses. Today I fear that too many politicians regard their responsibility towards business regulation as being to ask businesses how they wish to be regulated. Which is a more progressive position I suppose than that of the Department of Business which seems ideologically opposed to any sort of regulation.

So I think there is a hard truth in today’s world: that the voice of business carries vastly more weight with government than the voice of conscience.

As Spiderman teaches us: With that great power comes great responsibility. Because while slavery is sometimes an issue of organised crime it is more often an issue of the contemporary political economy. By that I mean it is an opportunistic crime practiced by unscrupulous people who see a chance to exploit others to their benefit as a result of constraints and enablements they discern in the law, regulation and custom by which we conduct employment, production and trade in the contemporary world.

One very real consequence of this political economy is that each of us in this room is probably wearing at least one garment tainted, at least in part, by slavery. Whether as a result of the use of state-sponsored forced labour of millions in the cotton harvests of Uzbekistan, or as a result of the enslavement of Dalit girls and young women in the spinning mills of Tamil Nadu in India, or some other aspect of forced labour, including child slavery, in the weaving, cutting, stitching or finishing of the garments that end up on our high streets.

Just to give one illustration of what that means in human terms: in the course of a piece of research into trafficking in garment manufacture in India Anti-Slavery spoke to the mother of one young 20 year old woman who worked in a cotton spinning mill there. She described visiting her daughter:

“I spoke to her in a room provided for visitors”, she said, “because visitors are not allowed to go inside the mill or hostel. My daughter told me that she was suffering with fever and vomiting often. …I met with the manager and requested him to give leave to my daughter because she was unwell. I told him that I would send my daughter back once she was better. But the manager refused saying that there was a shortage of workers therefore they cannot grant leave. He also assured me that they would take care of my daughter and asked me not to worry.”

A week later she received a message to say now she could collect her daughter. She was dead.

Now frequently when businesses are presented with evidence of slavery or other human rights abuses in supply chains their defence is “But we audit our supply chains!” Such ethical auditing has been going on for years now. So it is reasonable to come to some assessment of its effectiveness. And one of the things that is completely clear is that it has been wholly ineffectual in identification and protection of vulnerable workers, and wholly inadequate in bringing about any reform in the systems of production where forced labour and trafficking are so rife.

That should not be news to anyone because generally speaking the purpose of “ethical auditing” is to find nothing. And should some diligent journalist or non-governmental organisation ever expose the sort of exploitation that is routine in, for example, the supply of cheap garments to our high streets, there is no consequence for those businesses or for any business executives who have knowingly made decisions to source from slavery. Their goods are not excluded from European markets. The executives are not held criminally liable. I am not clear if the lack of extraterritoriality in clause 2 of the bill, the slavery offence, is deliberate in order to guard such executives further.

So the transparency in supply chain clause should not be seen as an end but as the beginning of a conversation on how we should seek anti-slavery reform of the contemporary political economy. But for such reform to happen will probably require business people such as yourselves to start the process. And I am encouraged to see a room full of businesses and investors – in fact, this may be the very first time such a large group of NGOs, businesses, investors and parliamentarians has come together to discuss modern slavery.

Investors in particular can begin to change the terms by which we conduct business by engaging on behalf of the ownership on how businesses are responding to the risks of forced labour and slavery in their supply chains. Business leaders can ask this question of themselves and of each other: Are you recognising the risks of slavery throughout supply chains and moving to credibly reduce those risks by ensuring basic protections of workers in those supply chains? Or do you find you are doing business with people who hide behind the comforting myths of ethical audits but in reality care little for the lives that are destroyed in far flung parts of the world because of their decisions?

Businesses must also, I think, begin to engage more systematically with government on these issues. John Ruggie, the author of the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, pointed out that businesses have the duty to respect the rights of workers while governments have the duty to protect them. But I am sure that many folk who are in this room today will attest to the fact that it is very difficult to respect the rights of workers if the relevant governments are, either through incompetence or design, failing to protect those workers.

The expansion of globalisation means that the international law governing this new approach to doing business becomes increasingly vital.

The risks of forced labour in international supply chains are compounded because, to use a legal metaphor, there is a prima facie case, I believe, that a number of businesses, countries and regions of the world are basing their competitive advantage on the use of forced labour. Anti-Slavery International investigations in India have shown how the routinized used of the forced labour of girls and young women is now a central feature of garment production for northern hemisphere markets. Further investigations in Thailand have shown how forced labour is a significant feature of production for export markets, most notoriously perhaps in the fisheries that supply prawns to our supermarket shelves.

In both these countries the failure of international rule of law is compounded by a failure of national rule of law. For Dalits in India, for Lao, Burmese and Cambodian migrants in Thailand, the notion of equal protection before the law would be a laughable notion if the consequences of its absence were not so tragic. In India the courts are so overworked that it would take hundreds of years to clear the back log of cases in Delhi alone meaning that factories that use forced labour of vulnerable workers, such as those producing cotton garments in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu, can act with virtual impunity. In Thailand, police describe migrant workers as walking ATMs, people to be harassed and extorted from not to be protected.

These are not just national issues. They are issues that should be of concern of British aid and diplomacy if Britain truly wishes to be an international anti-slavery leader. And they should be of concern to all of you if you have the slightest interest in doing business in these parts of the world.

Business must once again take a central role in leadership of the anti-slavery struggle. Businesses can begin with more rigorous investigations of supply chains with the intent to identifying and remedying problems that affect the rights of workers and communities rather than focusing primarily on managing risks to reputation and brand. Where the causes of slavery or other human rights abuses lie beyond the control of businesses, they are very well placed to pressure governments to do their job of protecting human rights.

Many of you will be aware of the challenges of forced labour in Thai fisheries. Anti-Slavery International is currently working with a range of UK retailers, many of whom are in the room today, on a unique pilot project to identify and address the risks of forced labour in supply chains and empower workers to access remedies. This work is very much about partnership between business and civil society, risk assessment and due diligence, rather than the traditional “audit” approach. At the same time, the work in Thailand highlights how governments are failing to protect workers in a range of industries and business can play a vital role in putting pressure on governments to act properly.

I regularly meet business and political leaders who are forthright in their opposition to the very principles of slavery. I am pleased to see that many of them have also recently begun to publicly show the depth of their moral courage by also seeking practical measures to end slavery. Many have added their voice to ours to send a strong message to the UK government on the importance of transparency in supply chains.

I regularly meet business and political leaders who are forthright in their opposition to the very principles of slavery. I am pleased to see that many of them have also recently begun to publicly show the depth of their moral courage by also seeking practical measures to end slavery. Many have added their voice to ours to send a strong message to the UK government on the importance of transparency in supply chains.

But all of us here have some measure of power to do more. As the Modern Slavery Bill reaches its very final stage next week, I would also like to encourage all of you in the room and especially those that represent business and investors to respond to the government consultation on supply chains. Your response will be key in ensuring that there is parity and coherence in reporting, that those businesses that lead the way will not be undermined by those who choose not to report or make minimal efforts to disclose.

I would also like to invite all of you to build on the collaboration across sectors and work further with civil society on addressing modern slavery.

We can turn away and hope somebody else we sort modern slavery out. Or instead we can grasp what opportunities present themselves to us and strive for reform and emancipation, and in the process help change a moment of history for vulnerable people across the world.