Summary: those who have lost their moral compass will never understand that protest is leadership

Rule of international double standards

Today, it appears that many Western political leaders apply multiple caveats to the principle of the universality of human rights. The result is that rather than rule of international law we seem increasingly to have rule of international double standards.

This is particularly plain in relation to British, American and German policy towards Gaza. In comparison with their supportive policy towards Ukraine and their outrage at Putin’s war crimes there, in relation to Gaza there is a lack of condemnation for ceaseless attacks upon civilians. On the contrary, the British, Americans and Germans remain publicly and materially supportive of Israeli policy.

The moral black hole at the heart of Western policy towards Israel

British, American and German policy on Gaza appears to be underpinned by a view that Palestinian lives are not equal to Israeli lives and so unworthy of comparable protection. Hence those three governments seem to have decided that it is better to arm and provide diplomatic cover for the far-Right Netanyahu government rather than to uphold the most basic principles of human rights and international humanitarian law.

In the face of the considerable evidence of genocide these governments are deaf to the international protests of conscience, and to the demands of Palestinian and Israeli voices for peace. Instead, they work to maintain the murderous Israeli Defence Forces supply lines at all costs.

I have heard some try to justify this human rights double standard in relation to Israel by responding to protests with patronising reference to the need for realism, for a “realpolitik” approach to the conflict. This is, perhaps, a notion they may imagine that the protesters do not have the sophistication to properly understand. However, many will know that “realpolitik” is a term that has considerable previous, notably in the hands of Henry Kissinger, as a euphemism for moral vacuity and acquiescence in crimes against humanity.

Given this many will remain unconvinced that “realpolitik” really is a sufficient justification for the mounting horrors in Gaza and the West Bank. So, why are the US, the UK and Germany so steadfast in their support of a far-Right Israeli government pursuing such a horrendous campaign of violence?

It is worth remembering that Germany was genocidal in Namibia well before the Nazis ever came to power. While relatively democratic, Britain and the United States were also genocidal in the 19th and 20th centuries in relation to, amongst others, Native Americans, Ireland and South Asia. It was democratically elected governments in the US that launched the invasion of Vietnam and the destruction of Cambodia. It was democratically elected governments in the US and UK that unlawfully invaded Iraq. Today it is democratically elected governments in the US, UK and Germany that have facilitated the far-Right in Israel in their indiscriminate slaughter of Gazan civilians.

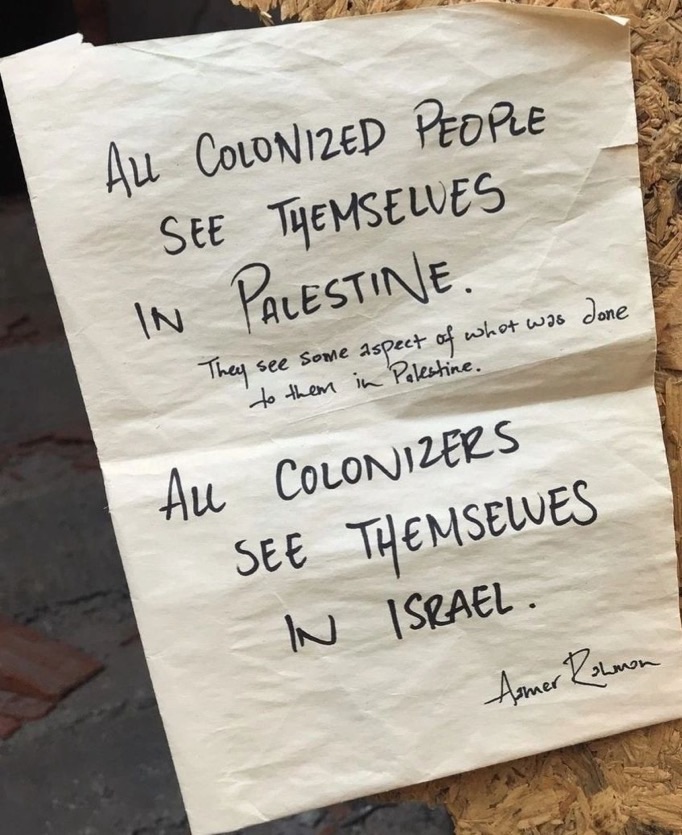

So, if we take even a medium-term historical view on these countries, it seems that there is a strain of thinking in those nations’ political cultures stretching from Left to Right that still view war crimes and genocide not as appalling and even unforgivable aberrations, but as legitimate policy options when it is convenient for them or those, however unsavoury, that they deem allies.

Protest as leadership

It is in this context that the leaderships of the US, the UK and Germany display such an extraordinary arrogance toward those protesting their disgust at their policies. In the UK, along with their gleeful grasping at graft, their contempt towards protesters is a measure of government ministers’ extraordinary sense of entitlement.

But it is the protests of which they are so contemptuous that so often change cultures and countries in the ways in which corrupt politicians can only dream. This is because protest is moral leadership that seeks to make the world a better place by demanding that it become so.

It is because of protesters that women have the vote, that apartheid has been ended in South Africa, that civil rights have been advanced in the US and the North of Ireland. When many governments have sought to merely manage the status quo – the “realpolitik” – protesters have asserted that this is not good enough and demanded better.

Today protesters understand, as the Irish patriot and human rights activist Roger Casement once put it, that “… we all on earth have a commission and a right to defend the weak against the strong, and to protest against brutality in any shape or form”.

So, at the end of the day, as Israel’s allies become ever more deeply mired in the murder of children, it is the protesters they disdain who will perhaps contribute most substantially to an end to apartheid in Israel/Palestine and thereby save the souls of their own countries.