Summary: an evolving collection of images of pieces about movements -in the broadest sense of the word – that have, by and large, stirred the conscience of the world, if only a little

Summary: an evolving collection of images of pieces about movements -in the broadest sense of the word – that have, by and large, stirred the conscience of the world, if only a little

Summary: second in a series of guest blogs from “Elphaba” on the ongoing war in Sudan

There was some great excitement in Singa this week as it was announced that many vehicles had been found and owners could bring proof of ownership and reclaim theirs. Ours was a battered, old, much-loved and very unreliable crate. She appeared to have some kind of sentience: working on a whim for some and not others. Opening and closing the windows was an act of will power (no winders that worked). But she had given great service carrying sheep, produce, people and everything in between for several years before she was taken at gun point last summer

A family member, Ax, went to see if she was there. He said the site was depressing. It was full of lines of metal shells, most with no wheels, broken windows and some with little or no innards.

At the back of his mind in going to look for the vehicle, apart from the fact that it is “something to do” when daily routines are still restricted, was a potential to get her back “in case we need to run”. But then you are an easier target in car than on foot. Behind this is the reality that although our family are for the most part fine, there is a thin ice feeling.

On the 4th October a friend in El Obeid rang and we were delighted to hear all was well. The next day he rang to say that they had been bombarded with drones. Omderman has also been hit. Nothing is resolved. And South Sudan is still unravelling.

One of the fall-outs of the war coupled with climate change (I think) has been a steep increase in Dengue fever. We also hear disputed reports of cholera outbreaks. Now at the tail-end of the rains is the malaria season

In the end we could not locate our vehicle. We laughed that she was never exactly a get away car, except in the sense that we seemed to get away with paying very little road tax over the years. In this seemingly endless war, the citizens who have lost most of what we think of as essentials are expected to pay significant amounts to reclaim their cars at a time that inflation in the costs of everyday needs, and the continuing devaluation of currency, bites.

Summary: The UK government’s shenanigans around Palestine Action undermines fundamental principles of rule of law

In 2010, Tom Bingham — former Master of the Rolls, Lord Chief Justice, and Law Lord — demonstrated in his book The Rule of Law that the concept is fundamental to any tolerably functioning democracy. He set out eight principles, including that:

• legal rights and liabilities must be determined by law, not the arbitrary discretion of, for example, ministers;

• the law must provide effective protection for fundamental human rights; and

• the rule of law requires states to comply with their obligations under international law as seriously as domestic ones.

The British government appears to violate all three of these particular principles in its decision to ban Palestine Action and criminalise anti-genocide demonstrators.

To begin at the beginning: there is no agreed definition of terrorism in international law and little academic consensus. The terrorism scholar Alex Schmid once suggested that terrorism might be considered “peacetime equivalents of war crimes.” That deliberately omits atrocities such as Hiroshima, Dresden or Gaza, but it is easy to see why governments responsible for mass civilian killings might resist such a definition that makes them seem at least terrorism adjacent.

In the absence of international agreement, terrorism becomes whatever individual governments decide it is. In the UK, the government has defined it broadly as violence against people and damage to property in pursuit of a political cause. Yet even by that standard, its application is arbitrary. The killing of close to 100,000 civilians by a UK ally is treated as legally too complex for ministers to judge, but the throwing of paint on a weapons system is not. To brand the latter vandalism as “terrorism” is to reduce the definition to a tool of political convenience — a textbook example of arbitrary discretion, and thus a breach of the rule of law.

This arbitrariness also undermines basic human rights protections, most clearly in the assault on the right to peaceful protest. On 6 September 2025, Steve Masters, a British military veteran, was arrested while sitting in his wheelchair in Parliament Square holding a poster. He was one of 890 people detained that day. Their “crime” was not violence, but conscience: holding placards in solidarity with Palestine Action. Farcically, many will be charged with terrorism offences.

What their protest reveals is the UK’s deeper breach: the failure to honour its obligations under international law, including its duty to prevent genocide under the Genocide Convention. Training officers of a military engaged in mass civilian killings, and rolling out the red carpet for those officers’ political masters, cannot plausibly be described as discouragement of genocide.

Protesters hold up a mirror to the British government, and the government recoils from its reflection. Yet it is only the protesters who offer any hope that the UK might one day be able to face itself with any self-respect, once the atrocities with which it has been complicit have passed.

Summary: citizens keeping the conscience of their country

Summary: First in a series of guest blogs on the war in Sudan, by “Elphaba”

I have been writing family bulletins for myself and anyone ready to read them since the start of the war in Sudan in April 2023. Kind readers have followed events that have driven my family from their homes at gun point from areas around Umderman to Gedarif and Singa. Then again from Singa as they went under siege there.

In an attempt to spread the burden of too many mouths to feed under one roof and much heart searching they scattered further. Some made the treacherous route to the north only later to face long electricity blackouts in April and May in the hottest time of the year. Others fled Singa on foot eastwards to Gedarif. From there one or two made it to Saudi Arabia where they have safety but at the cost of visa renewals and a deep sense of loss.

Now since the start of this year with relative peace in the Eastern areas of Sudan. For our family, at last, the kids are mostly back at school, the offices working and the economy working on some level. The banks work intermittently and cash is in very short supply. Some can use online banking with an app but for all everyday trading for basic goods, it is only cash. Adding to this, at some point in the year someone thought it a good idea to introduce a new currency and a new layer of potential confusion and corruption. In most of the East only the new currency works, while in the West only the old. In Khartoum and Wad Medani both get used.

With no immediate drama, I worry that we run the risk of joining the world in forgetting that the war and instability is far from over and accepting a new normal that is anything but. Now with the rains falling heavily there is very little seed to plant to benefit because infrastructure is decimated and only very few have any spare funds. And there is drama. For our friends in El Obeid and our once-home Dilling, siege, counter siege and fear have outlasted anything seen in the East and Darfur continues to be another story again. We last heard from close family friends there about a year ago.

As in Israel/Palestine there are huge profits and plans for still greater ones being made by those who would seize power and (ab)use weakness. In Port Sudan there are huge agricultural schemes under discussion not to mention rebuilding contracts and deals with the Gulf. It is mind-numbingly depressing in its logic of winner – eventually- takes all at whatever cost.

Meanwhile, for our family there is the on-going need to claw back dignity and rebuild with the resources we have. The young men – nephews and sons – working for low wages as labourers, drivers and other sorts of fixers send back what they can. They are themselves stranded in nearby countries away from their families and they know that whatever they send it is never enough. We are aware we have more than many and less than others.

I challenge anyone to fault the determination. My elderly sisters-in-law (elderly = 10 years older than me and in their 70s) have returned to their suburb in Umderman. There is no power. They returned to homes totally stripped bare “not even a teaspoon”. The first job for Nxxx was to buy a front gate as that too had been taken. Bottled gas costs 5 times what it did a year ago and anyway the cooker is gone. The widespread gossip that her neighbour’s son – now gone – whom Nxxx had known since childhood orchestrated the theft of her property and many others. And yet after a few days Nxxx at least is back in her house. As Rxxx explained to me from Saudi Arabia, her homesickness palpable: “of course all the family have been amazing. We are lucky. So much luckier than many. But you ache for what is yours, where you are you and where you’re not thought of a ‘a displaced’”

The violence has gone from these neighbourhoods for now and the young men returning have great plans to fix the power. Knowing the place well, I have no idea how they are getting by. I know it will be a profoundly communal endeavour. My 24year old nephew, his own life plans long since on hold returned from Port Sudan to help his father. He says they live on ful and ta’amia because that is made at a local shop where they have fuel. I imagine them all together much of the day to support, chat about possibilities, find workarounds to issues, talk prices and a future. I hope this will help them recover for now from the trauma of recent months/years.

The profound divide emerging in Sudan and the discrimination and racism that underlies the political stories is a worrying strategic trend that most Sudanese don’t have the luxury of considering. Maybe in that there are some universal trends.

Summary: Is high office worth the price of a soul?

In the Guardian profile of David Lammy on Saturday 2 August 2025 I was struck by one sentence: “On Radio 4’s Today, he [Lammy] energetically rebutts the suggestion that he hasn’t blocked all arms exports to Israel.”

This led me to check again what Lammy had said when announcing the suspension of some arms licences to Israel in September 2024. Then he said, “There are a number of export licences that we have assessed are not for military use in the current conflict and therefore do not require suspension. They include items that are not being used by the Israel Defence Forces in the current conflict, such as trainer aircraft or other naval equipment. They also include export licences for civilian use, covering a range of products such as food-testing chemicals, telecoms, and data equipment.”

That passage begs many questions. For example, is it possible to train pilots to drop 2,000 pound bombs on defenceless women and children without the use of British supplied trainer aircraft? Or how would the Israeli policy of banning Gazans from fishing in the Mediterranean be impeded if it did not have British supplied naval equipment? Those who have paid any attention to advances in the use of information systems in intelligence analysis for military operations will also wonder what role British supplied telecoms and data equipment have played in the Israeli identification and assassination of journalists, health and aid workers across Gaza.

Sophistry – the use of clever sounding arguments to deceive – is, of course, stock in trade of politicians. There is the stench of such sophistry in Lammy’s pronouncements on Israel, which remains a valued ally of the UK in spite of the extraordinary genocide that it has wrought on Gaza in plain view of the world.

In September 2024 Lammy asserted that, “There is no equivalence between Hamas terrorists… and Israel’s democratic Government”. To which one can only conclude that Lammy, desperate for high office, has, in the words of Orwell, submitted to the Party’s final most essential command: that he reject the evidence of his own eyes and ears.

On 2 August, the Guardian reported that Lammy “calls shooting civilians waiting for aid ‘grotesque’, ‘sick’; demands ‘accountability’ from the Israeli side. He says things are ‘desperate for people on the ground, desperate for the hostages in Gaza’, that the world is ‘desperate for a ceasefire, for the suffering to come to an end’”.

And yet, Lammy participates in a government that has continued the Tory’s policy of providing direct military support to Israel. As late as August 2025 the Jerusalem Post reported that the UK flies surveillance over Gaza to “locate hostages”. It should be remembered that that on encountering Israeli hostages, stripped to their underpants and begging for help in Hebrew, the Israeli Defence Forces shot them. So it seems unlikely that the Israeli government is interested in hostages as anything other than an excuse for more violence. In this context the UK’s “search for hostages” is likely a mere pretext for more general intelligence sharing.

It is possible that Lammy and the rest of the British government may finally be becoming squeamish at the level of killing in Gaza. But that does not absolve them of past complicity. Netanyahu and the rest of those that they have allied with have not changed. As a lawyer Lammy “ought to have known” that his allies were just going to do exactly what they said they were going to do at the start of the butchery.

Given the weakness of international institutions that the British and other Western Governments have contributed to through their complicity in Israel’s war crimes, Lammy and his colleagues in policy may yet avoid a criminal reckoning. But they will always have to answer to their consciences on whether the perks of high office were actually worth the price of their souls.

Summary: a survey of Greece and the Roman Empire from Homer to Hadrian

Robin Lane Fox may, for want of space, skim over some important subjects, such as the Peloponnesian War or the Year of the Four Emperors (69 AD BTW). But The Classical World is still a lucid and engaging narrative, and an excellent introduction to the sweep of that whole period of history.

It’s depressing to think that after some 2,500 years of history humanity has little changed: the abject supplication that the UK displays towards the US shows what empires expect of their vassals is little changed in millennia; today privileged poshos still think as little of committing genocide on foreigns as did democratic Athens or autocratic Rome.

But, as Lane Fox notes, some of the ideas from this time notably those of Socrates and particularly Jesus, offer a more hopeful ideal for humanity.

Given the depths to which western civilisation has sunk at this point in time, Jesus’ imperative to love our neighbours as ourselves still has a lot of heavy lifting to do.

Summary: American Hastings Banda

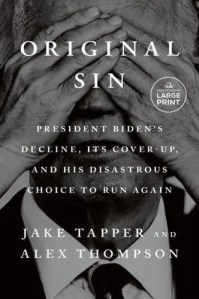

On a human level, this book is a very sad one. Across it, informants repeatedly refer to how their encounters with Joe Biden in the later stages of his presidency reminded them of their own impaired elderly relatives. Indeed, the descriptions of Biden’s deterioration within this book reminded me more than once of my father’s decline.

Of course, devastating as that was, I can be confident that no matter how afflicted my father became, unlike Biden, he would never have added his support to a genocide.

I counted four references to the violence in Palestine across this book, starting with a brief mention of the Hamas atrocity on 7 October 2023, and ending with another brief mention that Biden’s Gaza policy was the area of most substantial disagreement, in private, between Biden and his Vice President Kamala Harris.

This lack of discussion of one of the great moral issues of our day is, perhaps, unsurprising. Tapper and Thompson’s interests, like those of most Americans, are wholly US-centric. For them American preoccupations are paramount. And so they focus on the threat to American democracy posed by Biden’s cogitative decline and the opportunities that this gave to a resurgent Trump. They are uninterested in consequences of the moral collapse in international affairs of Biden and the swathes of the US political establishment that were their sources for this book. That doesn’t directly affect Americans.

This is somewhat disingenuous. There are occasional references through the book to Biden’s loss of support amongst young people. This is attributed solely to Biden’s age. Tapper and Thompson do not consider the possibility that abject disgust at Biden’s support for a racist and genocidal government in Israel could have deprived Harris of the small margins she needed in key battleground states to keep the presidency out of Trump’s hands.

In many respects Original Sin is a fine work of investigative reporting, and it does give important insight into the nature of power in the United States: Biden’s presidency gave power to a small cadre of advisers around him known, behind their backs at least, as the Politbureau. It was in this group’s selfish interest to deny to the world the fact that Biden was no longer physically or mentally fit to be president. To have done otherwise would have been a surrender of the power that they craved.

But the authors’ disinterest in the most murderous of Biden’s policies is reflective of one of the two original sins of the United States: that it was built on genocide and that many in the highest echelons of government still seem to regard this as a legitimate policy option. As a republic it has never quite grasped that human rights are meant to be universal.

Given this, it is difficult sometimes not to feel that in some grand Karmic way the United States deserves Trump: they reap now for themselves what they sowed so long for others.

Summary: calls for humanitarian aid are being used by pusillanimous politicians to distract from their failures to directly address the causes of humanitarian crisis in Gaza, most specifically Israel’s genocidal assault.

For over five years in the late 1990s I worked, mostly for Oxfam GB, organizing assistance, including water supply and sanitation, for the civilian victims of the civil war in Angola.

So, humanitarian response is a subject area I know a little about. As students of management and leadership will be aware, a problem with a bit of expertise is that you can presume that everyone understands the fundamentals as well as you do. This is called taken-for-grantedness in the literature.

I have been taking-for-granted that David Lammy and Keir Starmer – human rights lawyers after all, as they like to tell us, and therefore smarter than everyone else, as they like to imply – would understand the fundamentals of humanitarianism. After all, they have been pontificating on it since the start of Israel’s murderous assault on Gaza in 2023.

But maybe they don’t. Maybe it is possible that they are not the craven accomplices to war crimes that their ongoing military and diplomatic support of Israel suggests. Perhaps they are just pig ignorant of the vitally important stuff that successful humanitarian response requires.

So, here are a couple of the most basic lessons of humanitarianism for their edification.

1. The solution to a humanitarian crisis caused by war is not aid. It is an end to war. At the early stages of Israel’s latest assault on Gaza, Starmer and others attempted to deflect from their monstrous acquiesce in Netanyahu’s war crimes by rejecting the calls for an immediate ceasefire and instead calling for pauses in the violence to allow for the delivery of more aid.

The technical term for this position in relation to humanitarian response is “Oxford Union debating horseshite”. It is part of an approach to politics that values a plausible sounding point to win an immediate argument over the concrete measures necessary to resolve the actual causes of the crisis that the argument is about. Food assistance, vital as it is, does not protect from the other forms of collective punishment, such as the cutting of power and water that Keir Starmer advocated Israel doing, let alone the mass burning alive of children that Israel has routinised in Gaza since the outset of its violence.

2. If a belligerent nation is using famine as a weapon of war, then they are not going to permit humanitarian assistance unless put under robust pressure to do so. Robust pressure, not expressions of sadness or concern: Boycotts. Divestments. Sanctions. Criminal accounting.

3. If an assaulting army deliberately massacres humanitarian workers delivering food aid to hungry people, they are probably using famine as a weapon of war. Humanitarian workers not party to that war crime will therefore be made a target.

4. If an assaulting army on encountering their own nationals, stripped to their underpants and begging for help in their own language, shoots them, then that army is not on a rescue mission. Imagine what fate awaits those who cannot speak the attackers language. But you don’t have to because it has been documented by those the Israelis would seek to make victims. Indeed, the Israelis themselves have even videoed their own war crimes to show the world, so proud are they of what they inflict.

5. If an assaulting army is enslaving the civilian population they are attacking, then they are certainly not interested in any aspect of the humanitarian well-being of those civilians. In March 2025 the Israeli newspaper Haaertz reported that, ‘In Gaza, Almost Every IDF [Israeli Defence Forces] Platoon Keeps a Human Shield, a Sub-army of Palestinian Slaves.’

The British government used to like to depict itself as a world leader against slavery. But there has been a deafening silence from that government, and indeed much of the anti-slavery community, on this matter.

6. If you have soldiers in place to machine gun aid recipients, then the purpose of an aid distribution is not humanitarian. It is war crimes.

7. If you are materially supporting a political regime that has publicly stated its war aims are ethnic cleansing, then no amount of humanitarian assistance will mitigate that. You too are practicing genocide, even if you are also offering the doomed their meagre last meals.

Maybe these ideas are new to Starmer, Lammy and the rest of their government. But they are not hard. Indeed, tens of thousands of ordinary British people demonstrate that they grasp these most fundamental points already as, month in, month out, they gather in protests across the country to indict their own government for its abject moral collapse.

Summary: Remarks to the conference “Leadership in Dialogue: Exploring the Spaces between Ideas, Communities, Worldviews”, Birmingham, 8 to 10 December 2024[1]

There are diverse perspectives on leadership. Mine is leadership as a responsibility to choose – particularly in choices that affects the lives of others, in organisations or in wider society.

That has been most the defining feature of my experience of leadership, and something you never really appreciate until you are in that role. Key aspects of leadership involve decisions on resource allocation. Such choices are always fraught because there are always winners and losers, upset and distress, and lingering resentments.

Of course it can always be worse – I spend a good number of years leading humanitarian operations in, among other places, Angola during the civil war there. This led to some choices that were even more filled with anguish than the difficult but routine budget allocations that all leaders have to deal with. I write in my book, Ethical Leadership, about having to prioritize the lives of one group of people over another and how you have to learn to live with that after. That thought experiment with the runaway tram can get very real in some leadership roles.

So given that these are leadership realities, ethical leadership is self-evidently important: by ethical leadership I mean the attempt to make the most life affirming choice possible, irrespective of the difficulty of the situation. A life affirming choice is one that optimizes the protection of the environment on one hand and the protection of human rights on the other.

Now, when we are making choices it is important for leaders to remember that those choices are made in, what I call in my book “a cruciform of agency”.

That is, there are aspects of the choice – whether that choice relates to a love affair, or work, or war – that are in the social world: those are the rules and resources associated with the choice: the laws, polices, practice, finances or people who will be affected.

Then there are the personal aspects of the choice: the ones relating to the choice maker’s aspirations and experiences, and most fundamentally to their moral values.

The dialogue between these personal and social aspects of choice can be conceived of interacting orthogonally, hence the idea of a cruciform of agency emerges.

Now there is a 2002 paper by Craig and Greenbaum on a mining operation in South Africa. In that paper they recount how when they raised concerns with the mine management about issues such as health and safety, or labour terms and conditions, or the environmental damage that the operation caused, the managers they interviewed would express sympathy, but assert there was nothing they could do. The company they worked for caused the problems. Their responsibility was simply to get on with the job. They seemed to believe that they had no moral responsibility for the damage caused by the company despite the fact that it was they themselves who constituted the company.

This denial of personal responsibility of policy makers and business executives for the consequences of their choices is a central constraint on obtaining progress on many of the world’s contemporary problems including slavery, something that affects an estimated 50 million people in the world today.

I have rarely met anyone who has been in favour of slavery in principle. However, many in reality are in favour of slavery in practice. And if you doubt that, to take just one example, look at the hostile environments for migrants that many political leaders, from left to right in rich countries, take such pride in. This, despite the well documented fact that such hostile environments lead to the trafficking into forced labour and sexual exploitation of hundreds of thousands of vulnerable people.

If the personal aspects of leadership, particularly the moral responsibility of the leader for the consequences of their choices is abandoned then ethical leadership becomes impossible, and indeed much worse may emerge. But this is not uncommon.

You all know the history: The Nazi’s used the idea of “just following orders” to try to evade personal moral responsibility for their atrocities.

Henry Kissinger infamously used the notion of “realpolitik” to justify his murderous foreign policy that devastated the lives of millions in Bangladesh, Cambodia and Vietnam.

Today, Joe Biden, Olaf Scholz, Keir Starmer and David Lammy use the formulation “Israel has the right to defend itself” to justify their craven complicity in war crimes and genocide.

While the words used in each of these examples are different, their purpose is the same. They are explicit attempts to disguise moral bankruptcy and evade basic leadership responsibilities for the catastrophic human consequences of their choices. For this they deserve utter condemnation in “history and eternity” as Abraham Lincoln once put it.

The evasion of personal responsibility in a choice is the anathema of ethical leadership, and it brings with it a loss of authority: what follower worth their salt is ever going to respect a moral coward.

And there is always something more moral that leaders can do, even in the most extreme of circumstances. At the very least they can protest.

The current British prime minister likes to boast that his is not a party of protest. Which of course is true. Because protest is leadership. Protest is a way in which a society can open dialogue with itself and change the ways it thinks about itself.

Protest is sometimes the only way more formal dialogue with power can be obtained. Protest is how women’s rights and gay rights, minority rights and, indeed, all human rights have been advanced in the world. Protest matters nationally and internationally as the struggles to end apartheid in South Africa and bring some measure of justice to the north of Ireland have shown.

It also matters internationally because the failure of the West to protest Israel’s atrocities in Gaza, Lebanon and now Syria, compared to our volubility on Ukraine exposes an ugly, frankly racist, double standard at the centre of Western policy.

Much of the progress towards human dignity, including limiting contemporary forms of slavery, has been through advancing international rule of law. This avenue for progress has now been struck a grievous blow, because the profound undermining of the principle of the universality of human rights that Western policy towards Gaza has asserted. This has undermined in a fundamental way the ideal of an impartial system of international rule of law.

Many European leaders are expressing concern at the threat that Donald Trump poses to international order. But the damage done to that system of rule of international law by Biden, Starmer and Scholz is already catastrophic.

At the heart of ethical leadership is the ideal once set out by the Irish patriot and anti-slavery campaigner Roger Casement who said, “We all on earth have a commission and a right to defend the weak against the strong and to protest brutality in every shape and form.”

That is a commission which we must all take up. Because, more than any other time in my life, the challenge for all of us to lead ethically is at its most urgent. We are all leading in the grey zone now. Indeed, it is almost night.

[1] In his essay collection, The Drowned and the Saved, Primo Levi wrote of the “grey zone” a morally ambiguous space where the ideas of right and wrong are no longer absolute and “good” decisions are impossible.