Summary: Netanyhu’s war is racism and should be condemned as such

Perhaps I have missed it, but I have not seen many anti-slavery organisations condemning the mounting slaughter of civilians in Gaza, and now Lebanon, over the past year.

I wonder about anti-slavery organizations more than other specialist NGOs or human rights issues because, for the past 20 years this has been my principal area of professional practice and so is a sector with which I have some familiarity.

Perhaps some anti-slavery organization feel that something like Gaza is not part of their mandate and so would be inappropriate for them to raise their voices. Perhaps others are afraid of upsetting donors by raising question about another specialist area – human rights in war – and losing funding for other important work. Maybe others are afraid of annoying the governments of the US, UK and Germany, or certain parts of the EU Commission, who may be complicit with the policies of Netanyahu’s cabal and so losing precious access and the occasional invitation to convivial cocktail parties.

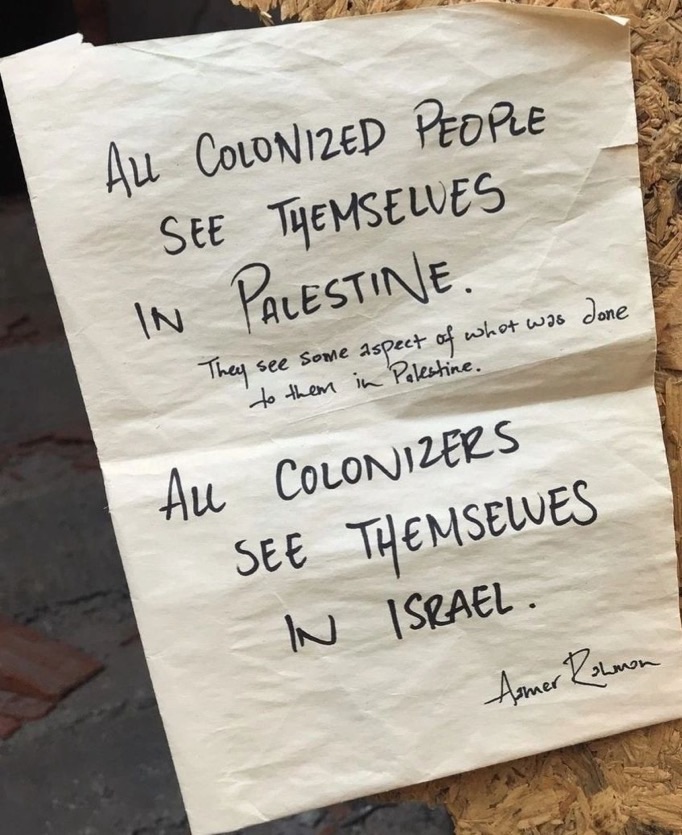

The thing is this: if we survey the realities of slavery through history right up to the present day we see very clearly that it is rooted in racism and the dehumanisation of others. Hence, anti-slavery organisations must be anti-racist if they are at all serious about tackling the causes and consequences of enslavement. If they fail in that fundamental then they are not truly anti-slavery. They are merely performative distractions.

Consider now Benjamin Netanyahu’s reference at the start of the assault on Gaza to the Amalek, a nation that, according to the Bible, King Saul was commanded by God to kill every member of. Consider the Israeli blockades of aid to Gaza to deploy famine as a weapon of war, and Israel’s vote on 28 October 2024 to, in effect, ban the largest provider of humanitarian assistance to Palestinians, the UN relief and works agency (UNRWA). Consider how IDF soldiers can cheerfully make videos for TikTok of their demolition of homes, schools, universities, hospitals and every other vestige of civilian infrastructure that makes Gaza habitable. Consider now Israeli Defence Minister Yoav Gallant’s description of Palestinians as “human animals” as he called for a “complete siege” on Gaza, an imposition of collective punishment that is illegal in international law.

Each of these examples, and there are many more, is a naked expression of racism against a whole people. Racism is at the root of every atrocity that is committed by Netanyahu and his cronies.

The continued acquiescence of US, UK and Germany in this, up to and including the provision of money, material and intelligence to sustain the Israeli offensives, in spite of overwhelming concerns regarding both their morality and legality, has dealt a grievous blow to international rule of law. It has also done something that would have seemed unbelievable a mere 18 months ago. It has established a credible case that there is no moral difference between the foreign policies of Biden’s America, and Putin’s Russia. Both appear ready to shred law and the most basic principles of human rights when it is convenient for them.

It is upon meaningful rule of law and a common adherence to the fundamental principles of human rights that the cause of anti-racism, and anti-slavery, have been advanced. Now, however, if campaigners challenge transgressing governments that their policies are in breach of human rights many will laugh and point to Gaza and Ukraine and say that the US and the UK, Germany, Israel, and Russia have demonstrated that the only right is might.

So, every anti-racist organisation on this planet, and that includes all anti-slavery organisations that are worthy of the name, and every organisation that derives its mandate from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, must add their voices to the international condemnation of the Netanyahu government’s racist wars. If they do not then they will seem as hypocritical as the western governments who facilitate these wars in spite of the mounting evidence that the bloodshed that Israel perpetrates is foul murder.

As the Irish anti-slavery campaigner Roger Casement put it, “we all on earth have a commission and a right to defend the weak against the strong and to protest brutality in every shape and form.”

That commission was never more urgent than it is today as we daily bear witness to Netanyhu’s unfolding policy of genocide.