Summary: Two masterpieces of Second World War history that show the terrifyingly human face of the monstrous

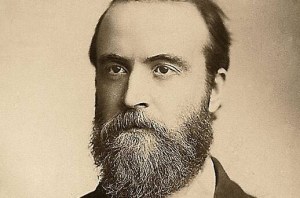

Gitta Sereny’s subjects in these two seminal works are the war crimes and the industrialised genocides of the Nazis. But, as the prisms through which she explores these issues are the biographies of Franz Spangl and Albert Speer, she never loses sight, or lets the reader lose sight, of one of the most troubling truths about these, and all, atrocities: that the war criminals and monsters who perpetrate them are as human as any one of us.

Speer was, amongst other roles, Hitler’s armaments minister and Sereny’s biography of him is rich in detail regarding the management of Germany’s wartime economy and Speer’s exceptionally effective efforts in keeping it functioning in the face of Allied bombing, Nazi in-fighting and Hitlerian fantasy. Stangl was a provincial police officer, transferred into the Nazis’ early experiments of murder with their “mercy killing” programme, and finally “promoted” to manage the death camp at Treblinka. The two biographies therefore provide chilling insights into both the highest echelons of Nazism and the horrific consequence of the decisions taken there.

Sereny’s thorough research into her subjects included extensive interviews with both men. Almost of necessity she came to establish considerable sympathetic understanding with them. But she never lost sight of what they did. Her conversations in Dusseldorf prison with Stangl forced him, with devastating personal effect, to finally acknowledge what he had done. Speer, a much more intelligent man, arguably one with the potential for greatness, was altogether a more slippery character, and so much more sophisticated in evading, even to himself, similar acknowledgement of his measure of responsibility for the crimes of the Nazis. At the end of the war he had all but deluded himself into believing that the Allies would ask him to help lead in the reconstruction of a devastated Germany.

In spite of the bleakness of the books’ subjects they are not devoid of heroism: In Into That Darkness Rudy Masarek, a leader of the Treblinka uprising, stands in telling contrast to Stangl; in the case of Speer Claus von Stauffenberg, the leader of the 20 July plot against Hitler, stands in juxtaposition. Though they appear only fleetingly in the pages of these books the lives of these men, with their exceptional moral and physical courage, powerfully indict the evasions of both Stangl and Speer. These were men who came from similar backgrounds but whose moral choices were diametrically opposed to everything that Stangl and Speer came to stand for.

These are amongst the most extraordinary and important works of non-fiction of the 20th Century. They are compelling studies of the descent into evil of one ordinary man and an extraordinary one. They are powerful, elegantly written, gripping and vital for understanding how close to the abyss human beings and human society still hovers.