Summary: The myth that violence solves problems persists despite history often proving the opposite.

At the end of John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men, George shoots his friend Lennie. Lennie, a well-meaning but simple-minded man, does not understand his own strength or the fragility of others. So, he has accidentally killed a young woman, and George knows that if the mob reaches him first Lennie will be tortured before he dies.

Steinbeck understood something that popular culture often forgets: violence rarely solves anything cleanly. Yet in cinema it frequently does. From Westerns to modern action films, societies’ problems are tidily resolved by lethal force.

Wyatt Earp invariably sorts out his society’s ills by use of his six-guns. James Bond’s liquidation of supervillains always makes the world a better place.

The satisfactory resolution of daunting problems through the use of violence is so commonplace a trope in cinema that it is perhaps now as deeply embedded a cultural idea in the West as that of Santa, and the Easter Bunny. However, unlike these last two myths, some adults seem to continue to believe it.

Put another way, in spite of the vast historical evidence to the contrary, they believe that the most complex of geo-political problems can be solved, as Eddie Izzard’s character says in the movie Valkyrie, “with the careful application of high explosives.”

Anyone who has any experience of actual war will attest that the matter is much less clear-cut. Violence tends to be the bluntest instrument in problem solving, often ineffective and opening as many new problems as it was meant to resolve.

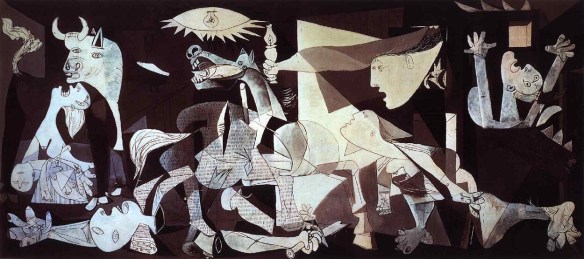

As Shakespeare warned, in war the dogs are let slip. The ensuing carnage leads to the ties that bind society being sundered, civilians being slaughtered in even the most “surgical” of military strikes, and the infrastructure of daily life being decimated.

There may be diverse reasons that people celebrate the unlawful 2026 US-Israeli assaults on Iran and studiously ignore the piles of children’s corpses that have resulted. What those celebrating have in common is a lack of empathy with the innocent falling under the weight of metal, and a lack of imagination about what will transpire. In particular, they fail to conceive of the legacy of bitterness that will result.

Violence rarely ends a conflict. More often it plants the seeds of the next one. As James Baldwin noted, “The perpetrator always forgets; the victim never does.” Societies that know little history never learn this truth. That has long been true of much of England. It is also true now of the United States.

Anyone who watched the Tucker Carlson interview with US Senator Ted Cruz will have been struck that US foreign policy is being made now by the spectacularly ignorant. Cruz did not even know the population of a country he thought the US should invade.

Such people are malicious contemporary equivalents of Steinbeck’s Lenny – simple-mindedly disdainful of complexity, absent of empathy, and contemptuous of those who are fragile before their military strength.

The world is currently in the hands of such dangerous buffoons, people who treat violence as a solution and assume they will never face consequences for the murderous destruction they unleash.

Even Steinbeck would be at a loss to find a neat narrative resolution to deliver us from their evil.